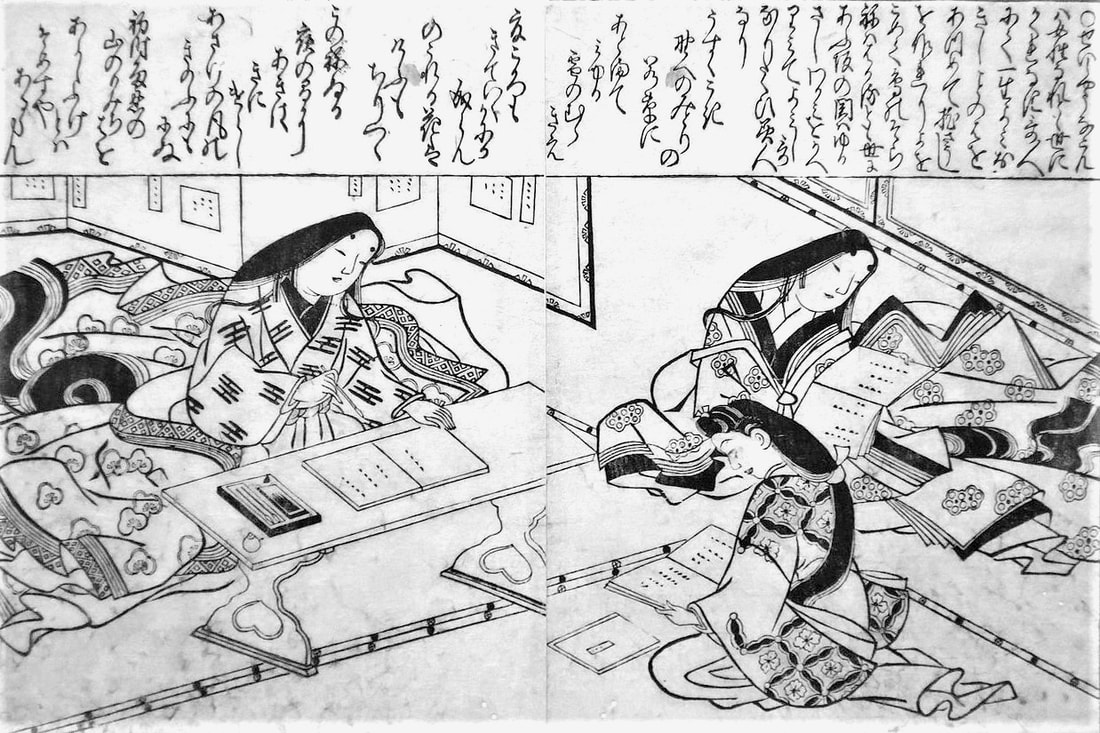

A depiction of diarist Sei Shōnagon with attendants, c. 1683. Photo via Wikimedia Commons When I go to thrift stores, I always make sure to snoop around the used book section. Thousands and thousands of pages full of writing, lying there to collect dust. What overlooked insight might they contain? Often, unfortunately for me, not anything particularly interesting. Dr. Phil’s advice on how to lose weight; a wrinkled, old, lurid romance novel featuring its authoress, Joan Collins, on the cover in full Dynasty garb; kiddy books given away once their readers have grown too old. It’s the thrift store, not the Library of Alexandria, and I know not to expect much. Instead, I know to walk the aisle like its a graveyard, ruminating over the stories these dead books contain, paying my respects to the Halo novel whose cover is completely torn off, and appears to have suffered water damage. Every so often, however, I come across something mildly interesting, at the very least. It was a journal with Anne Gedde photographs of babies in flowers interspersed between its blank, snow-white pages, waiting to be written in—all but one, that is. A single page was fully tattooed with blue ink. I felt a thrill when I saw that on February 29th, 1996, a teenage girl decided to take a brief snapshot of her life: “I feel that I have no one to tell my thoughts and feelings. Today was a good day, but then again I try to make every day a good day. My parents always hold these standards that I have to meet up to and sometimes I wish I could just forget them. I can’t, so I work hard in school, but it always seems that I don’t work hard enough. I’m a little worried of what’s gonna happen to me, but I guess I’ll just have to wait and see. I’m gonna try to keep this journal and write in it periodically. Besides, I need somewhere to keep my thoughts and this is just the thing I can keep them in.” Needless to say, her experiment in keeping a journal failed after that one day. So, what of it? Maybe I’m a nut, but writing, as a way to put a hold on and process our complex emotions and experiences, absolutely fascinates me. Here is the brief, inconsequential rambling of a random, worried teenager from two decades ago, and here I am, sympathizing with a stranger who I’ll likely never meet. Hopefully, the author is still alive and well, and doesn’t even remember scribbling her thoughts onto that page. Whatever troubles she faced at the time, may have faded, or more likely evolved into different, more complex struggles. I can reflect on the times I have felt the same way as she did, and I recognize ways I have both moved on and fell back into those feelings. The fact that she never wrote in that journal again tells a story in itself. Perhaps that leap day in 1996 was just one bad day where she couldn’t contain her thoughts. Maybe she got too busy living to dedicate time to writing. Maybe she questioned her choice of a journal, and didn’t want photos of babies mixed in with her confessions. It was just a little page of messy thoughts, and yet, it made me feel nostalgic for a life I’ve never lived. In fact, it has me thinking of the strange times I’m living in now, and the others living it beside me. Everyone has their own story to tell. Everyone has their own unique lens through which they view the world. And yet, our stories are all intertwined. Writing opens our hearts and minds to feeling understanding and connection towards ourselves, others, and life itself. Whether we, as writers, are exploring unanswerable questions, or we, as readers, are sympathizing with them, there is something universal and miraculous about this very human invention. Writing—even as a completely private endeavor—encourages us to understand and explore the ways that we and others view the world. Writing can be like a mirror to our own humanity. Sei Shōnagon, a noblewoman who lived in 10th-century Japan, is one of the world’s most famous diarists. Although her diary, “The Pillow Book,” was intended for her eyes only, for centuries, it has offered colorful insight into classical Japanese high society. It has also enthralled its readers with a vibrant capture of the author’s wit, perception, and personality. “I love the way, when the sun has risen higher, the bush clover, all bowed down beneath the weight of the drops, will shed its dew, and a branch will suddenly spring up though no hand has touched it. And I also find it fascinating that things like this can utterly fail to delight others.” The fact that, through writing, I am able to read the thoughts and experiences of a person I will never meet—that we, as humans, invented this form of communication—fascinates me to no end. Despite time and distance, I can almost see what she saw. I can almost feel how she feels. Writing, like a photograph, can almost capture our complex societies, feelings, and souls. Even when we are only writing for ourselves, there is value in making sense of our experiences. Even if it’s trivial. Even if we’ll burn it after. Even if it will end up collecting dust in the back corner of a thrift store. And as we navigate this busy world, often foregoing any reflection at all, I, also, find it fascinating that things like this can utterly fail to delight others.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed